Want to learn one of the principles that Airbnb uses to delight its customers – something that’s founded on hard science and that you can use in your designs? Then read on.

Recently, when I was using Airbnb, its design made me appreciate the principle of chunking in UX design. It demonstrates how to use chunking to delight customers: Airbnb breaks down relevant information on the website into small, easy-to-digest pieces, making it palatable for the users so they can find their desired choices easily.

Chunking is a concept that has roots in cognitive psychology. The term was introduced in 1956 by George A. Miller, a luminary in the field. In his paper, Miller asserted that human memory is limited to around 7 (plus or minus 2) pieces of information and suggested breaking down or organizing different kinds of information into chunks for people to easily remember what they see.

The above figure shows how a designer follows the principle of chunking. As the name implies, chunking means the grouping of information into familiar, manageable units called “chunks”. Designers do this so the content or information they chunk can be easily processed and remembered by anyone who encounters it. For example, a chunked phone number (+1-234-567-8901) is easier to remember (and scan) than a long string of non-chunked digits (12345678901).

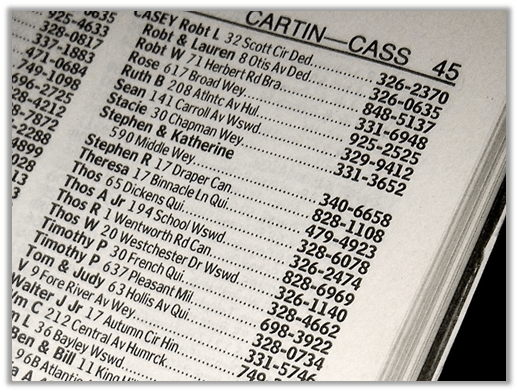

Take a look at the image below, where an old phone book proves its designers got the principle of chunking right. A major design challenge of compiling a phone book is that it has to list many numbers on each page. However, because these are chunked, users can find contact numbers fast and read these easily.

From a UX standpoint, when designers break up content into small, distinct chunks—rather than drown users’ eyes in an undifferentiated sea of atomic items of information—their output has several advantages, such as:

- A user interface (UI) which is easily organized, creating a good first impression.

- An overall good UX that leaves users feeling satisfied as they have found what they were looking for.

In the figure below, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), one of the longest-established and most widely recognized providers of news (radio, television and online), has followed the principle of chunking to present its news items. The BBC has split each news item into different chunks or sections such as technology and sport, and used short sentences in its news headings, combined with generous amounts of white space. Since the BBC has followed the chunking principle (i.e., grouping all UI elements into individual chunks which are easily recognizable and comprehensible), users can easily:

– Find and read a news category they are interested in.

– Find and read a news item within their category of interest.

Apart from this, the BBC’s use of the law of chunking enables it to fulfill its primary purpose as a news site – namely, to get users to read the news. Finally, because the information is so well presented, users also find it aesthetically pleasing – and so they get to enjoy a good UX overall.

Along similar lines, I used another website to try to book a hotel room. However, on Hotels.com I found I had an overall bad experience, mainly because the layout of its UI was cluttered and not neatly chunked. On the other hand, I found the overall UI and the entire process of making a booking through Airbnb a charm, thanks in part to how easy it is to both search for and book different accommodations on its website. Airbnb provides nicely chunked content, which creates a wonderful first impression of its UI to the user. Airbnb also did not overload me with tons of information. So, it made the whole booking process just so seamless for me. Let’s discuss both of these examples in detail now.

Bad design: Hotels.com

As someone who repeatedly juggles with and switches across many different tasks, I can lose my focus all too easily whenever I encounter a lot of information. As a user, I don’t want to waste time trying to figure out where to find things on a website. It has to be a simple “Click here, finish your task and leave” kind of flow for me – that’s one hallmark of a seamless experience. The science agrees with me here. If you recall Miller’s law, the average person can only keep 7 (plus or minus 2) items in their working memory. From a UX standpoint, any information which is being conveyed should then be organized into small chunks for users to understand it easily. However, the UI of Hotels.com did not follow Miller’s law, and the different elements in the UI were not organized as chunks. In fact, they were more cluttered, which made it difficult for me to find my way around.

For instance, please look at the image below. When I tried to book a room in Dublin, I filtered the accommodation options based on their distance from downtown Dublin. As you can see, it gave me an enormous list of different areas in and around Dublin, which are not necessarily famous landmarks or places I would be aware of.

Having such lists is the opposite of what the principle of chunking advocates (recall that chunking calls for information to be presented in small blocks or chunks). Not only is such a list an example of a poorly chunked UI, but it is also just downright confusing for me. The reason is that I have no idea of how far half the areas listed there are from the central business district of the city. I would need a map to tell me. It would have been useful to have different chunks of landmarks displayed side by side with minimal content, which—as I’ll explain later—Airbnb does very well. Due to the lack of chunking and the organization of UI elements (more specifically, the distance filter when booking the accommodation), I found that my overall experience with Hotels.com was confusing and taxing. I had to stop and spend time figuring things out. In today’s culture of information overload, that’s something which anyone associated with design needs to steer clear of.

Another example of poor chunking in the UI of Hotels.com is how they have arranged the search using a View on map feature which allows a user to see all listings of available lodging in a particular area.

As I have marked with a red arrow in the image above, whoever designed this for Hotels.com actually made it difficult for me to find this feature, as it is out of my line of sight. Furthermore, the box which says “view on map” is very small and is near the top-left-hand corner of the website. In my experience, that is an area generally not associated with a map search feature. The advantage that UX designers have when they apply the law of chunking is they can leverage a user’s working memory and engage more users with appropriately chunked UI elements. For instance, in this case, a UX designer could run a usability study to pinpoint where exactly in the Hotels.com website that users would prefer having the map feature. Then, armed with the results, they could chunk the UI elements accordingly by following Miller’s law.

Finally, Hotels.com gave me many options to filter from the menu on the left-hand side, but this is once again a violation of Miller’s law. If you look at the image below, I have to scroll a long way to see all the categories of options they offer for me to pinpoint the accommodation I would like. There are over 10 of these categories, which are just displayed as lists and not in any particular order which I can see. By the time I reach the end, I just feel like giving up on booking my stay. To optimize their UX, Hotels.com should follow Miller’s law and have these choice categories in the range of 7 plus or minus 2 (i.e., 5–9) so that the UI elements are easily comprehensible.

Hotels.com is an example of what I would call bad UX design. For one thing, its design is an apparent violation of Miller’s law where I should be able to keep 7 (plus or minus 2) items in my working memory, hence why I found the website cluttered. What’s more, I found it increasingly frustrating to scroll for so long before I could figure out which options I needed to check to proceed with my booking. Also, the website’s designers do not seem to have adhered to good chunking practices. The idea behind chunking is that every part within the UI is spaced at regular intervals so all of them are clearly legible. That means they should be in the user’s line of sight and just easily comprehensible overall. With this in mind, Hotels.com could benefit substantially from a thorough UX evaluation study.

I just wish I could perceive all the information as chunks. That way, I could make sense of it more easily. As Steve Krug, a usability engineer, in his influential book Don’t Make Me Think famously said (and words that I feel make me reflect on my interaction with the Hotels.com website):

“The fact that people who built the site didn’t care enough to make things obvious—and easy—can erode our confidence in the site and the organization behind it.”

Another bad design example: Receipts

I have kind of an obsessive habit of saving my receipts until the end of the month so I can track where my money is going. To me, it’s a normal part of money management that unfortunately can get rather labor-intensive from time to time. That’s because of the layout of many of these receipts. In fact, these things often present themselves as classic examples of a lack of chunking. Many times, I just can’t understand what exactly is on there! Although I always have my wits about me when I’m making purchases, by the month end, when it comes to checking all my receipts, I frequently go “Now, what was that for again?”! 😊

To put this in context, recently I paid for excess luggage at an airport. The receipt from this transaction appears below:

From the receipt, I cannot figure out two things, which is a concern to me. So, I am left wondering:

– What exactly have I paid for?

– What do the different numbers mean?

From a chunking standpoint,

- There is no structure to the receipt.

- It presents an enormous amount of information which I find cryptic.

- It is not user-friendly. After all, a receipt should be easily readable for the person who made the payment so they can see—at a glance—what they paid for. ‘However, a larger point is that, with some transactions (e.g., in supermarkets) customers can occasionally be overcharged, and having a clearly understandable receipt gives them the assurance they desire. More often than not, such a receipt would just end up in the garbage!

Altogether, these points can easily amount to another problem: confusion, leading to a loss of trust. To illustrate how design makes the difference, let’s look at two scenarios. If you consider how you buy groceries from your local supermarket on a typical day, if you’re anything like me you’ll watch each item appear on the screen as it gets scanned. And the receipt is likely going to be clearly itemized and accurate.

Now, please picture yourself in a more rushed situation and far from home: You’re in a foreign country; you’ve had to buy something in a hurry, and the receipt comes out looking something like the one I showed above. Perhaps you thought nothing more of it at the time because you had to catch your plane. Later, when you’ve got time, you start to wonder: “Was that right?” or “Did they overcharge me?”. The language barrier probably doesn’t help, but the most important point from a design aspect is the visuals. When the text is mashed together and you have to work to decode what it all means, the designers responsible have failed in a fundamental task.

To improve the overall design of the receipt, a designer should follow the principle of chunking. With chunks or organized sections within the receipt such as product name and card ID, it will have structure and become more human-centered.

It would be as if….

Let me use an analogy to show how bad an “unchunked” design can get. Imagine you’ve just sat down at a brand-new restaurant and are looking at your menu. A waiter is hovering over your table, asking if you have any questions. As it turns out, you do, but it has nothing to do with the dishes themselves. You want to know who designed their menu. Why? Because, to your complete amazement, all the starters, entrees (or main courses), desserts and drinks aren’t chunked into the nice, tidy sections which you would expect from a normal menu. Instead, they’re all stuck together in one list – you have to wade through a long slab of text. In fact, this menu is so difficult to make sense of that you nearly get up and leave. Only your gnawing, ever-worsening hunger keeps you motivated to cut through your confusion and just pick something before you starve. Now, if you had to actually sit through an experience like that, would you ever go back to that restaurant? Even if you finally enjoyed a well-prepared meal there, could you honestly recommend a dining establishment with a menu that confused its patrons so badly?

What can we learn from this?

One common denominator I see in the receipt and Hotels.com examples is that their layouts lack the chunking I need to be able to easily find the information I want. There’s too much going on for me to digest all this cluttered data comfortably. In both instances, I can spot a violation of Miller’s law of keeping chunks to 7 ± 2 (i.e., 5–9) items.

Finally, whoever designed the website for Hotels.com and whoever designed that receipt format did not seem to have the best interests of all their users in mind. For instance, if I have to book something in a hurry and on my phone, I want to see that designers have considered my context. The longer a user takes to figure out what to do on a website or exactly what is what on a receipt, the greater the chance they will become puzzled or frustrated. In technical terms, a design that causes them to feel that way is not a user-centric one.

Enter Good design: The Case of Airbnb

Airbnb is an inspiring example of how you can create a great user experience by putting relevant information into blocks or chunks. Airbnb has used this principle to powerful effect and addresses all the earlier deficiencies in design I pointed out with Hotels.com. For instance, I searched to stay in Bruges, Belgium, using Airbnb’s website, and this is what it looked like:

Airbnb, in my opinion, follows the example of chunking by grouping information into easily palatable elements. For instance, when I search for “Bruges” along with the dates, the results show 7 filtering options – as you can see in the annotated figure above. Notice how the emphasis is on a simple, clean design which is easy to understand and does not make me think. Not only is this aesthetically pleasing, but the design also does not overwhelm you, thanks to the fact that whoever designed it observed the law of chunking and kept chunks to Miller’s all-important 7 ± 2 items. So, following Miller’s law plus good chunking practices equals an awesome UX!

If I click on the last option (more filters), a new menu appears with 9 additional filters, each with chunked subcategories. As the image below shows, there is a “Rooms and beds” filter with the subcategories “Beds”, “Bedrooms” and “Bathrooms” where I can choose my preferred number of each. The point here is that I found all of this information on Airbnb to be much more easily viewable than what I encountered on Hotels.com, simply because Airbnb follows the law of chunking and its designers prove they adhered to Miller’s law when they were designing the UI.

While the total number of filtering options available in Airbnb’s search exceeds the magical number 7 (plus or minus 2) I discussed earlier, the design is still neatly chunked. That is, Airbnb uses categories and subcategories within this UI to chunk information, making it easy for users to navigate and find the filters they need without them getting lost or overwhelmed. Quite clearly, Airbnb has invested in design thinking and has paid a lot of attention to following good chunking practices. Clearly, the upshot of that is a user-friendly website which I enjoyed encountering because it was so easy to use.

If we think about it, most of the products and services we see around us are designed for us to use in one way or another. Therefore, should they not be easy to use and make our lives easy, too?

Lessons learnt and best practices:

- Break relevant information into small chunks and make it palatable for users so they can easily find their desired choices.

- Follow Miller’s law and keep chunks to 7 (plus or minus 2) items to:

- Present content more memorably and effectively.

- Decide how much to show users at one time (and what to cut out).

- Invest in design thinking (i.e., sit down with your users, identify their pain-points, challenge your biases and always think along the lines of “How can I make this easy for the user?”).

- Always test your designs – once you have a prototype ready, ask the users if this would be an experience they would enjoy.

The next time you frown at an instance of bad design, stop to think. Determine why the design failed, find examples of designs that did things right and make a mental note of the lesson/s you’ve learnt.

Want to learn more?

Are you interested in exploring the intersection between UX and UI Design? The online courses on UI Design Patterns for Successful Software and Design Thinking: The Beginner’s Guide can teach you skills you need. If you take a course, you will earn an industry-recognized certificate to advance your career. On the other hand, if you want to brush up on the basics of UX and Usability, try the online course on User Experience (or another design topic). Good luck on your learning journey!

References:

- http://ui-patterns.com/patterns/Chunking

- https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/book/the-glossary-of-human-computer-interaction/chunking

- https://www.nngroup.com/articles/chunking/

- http:// https://www.freshconsulting.com/uiux-principle-47-chunk-information-to-make-it-digestible/

- http:// http://www.uxness.in/2015/08/the-chunking-way.html

- http:// https://medium.com/@Ana_Pierce/chunking-f25ddf9eb838

- https://www.trymyui.com/blog/2018/08/21/5-psychology-principles-better-ux-design/