Writing user surveys is a difficult undertaking; it is truly a form of art.

The expertise of our team at User Conversion consists of various UX researchers, user psychologists, UX designers and web analysts. However you may be surprised to hear that even with all these specialisations, we still regard writing surveys as a difficult task to undertake. There are mistakes that we find fairly common when reviewing the effectiveness and efficiency of a user survey – from the design, to the audience, to the analysis.

Here are the 5 most common mistakes we often see when writing user surveys.

1. Objectives

There are two types of objectives when writing a user survey: The

- Overall objective(s)

- Individual objectives

I find the latter as particularly interesting since I regard the setting of individual objectives as being the most difficult to get right. Setting individual objectives for your questions helps you focus on what each question is supposed to achieve. Most get stuck in a trap of “What other competitor products have you used before?” or “How did you get here today?” – questions that, when you really ask yourself, do not provide that much insight. Don’t get me wrong – these questions are fine for funnelling, but ask yourself with every question you write: “What insight is this question going to give me?” Or, as Jen Havice, Conversion Copywriter & Head Honcho at Make Mention puts it, “Don’t waste your time or your respondent’s patience with questions you’re simply interested in knowing the answers to versus ones that you need the answers to.”

When writing for conversion optimisation, always ask yourself “what can this question give me?” and always question, therefore, the efficiency of your own survey design ability. As a result, we recommend you structure user survey questions as follows:

- Objective: The individual objective of the survey question

- Question: The question that you are asking

- Answer: The answer type or possible answers related to the question

2. Scaling Questions

“There are lots of very fundamental errors in survey design – the first one ironically is a scaling error I see all the time” states Dr Rob Balon.

Dr Balon is the author of four books on research and marketing as well as the CEO of The Benchmarking Company, a market research and consulting firm for clients including Bloomberg Financial and Dell Computers. He describes scaling errors as the most common. Simply put, scaling errors occur when using a 5-point scale that has 5 as the most positive value and 1 as the most negative.

In an article on ConversionXL, Alex Burkett discusses more about survey response scales and explains survey scale best practices in quite some detail. More specifically, Jared Spool of UIE, states that in a five-point Likert scale “we think that people can’t just be satisfied or dissatisfied, we’re going to enhance those with adjectives that say “somewhat” or “extremely.”…” He continues to relate “extremely satisfied” to “extremely edible” – it is a non-meaningful term. Really, we should be using language like “delight” or “frustration” – terms that really tell us more about a user’s attitude rather than acceptance.

3. Language

Thinking that the language of the survey is not relevant to the target audience can be a standard mistake in user survey design, through either assumptive verbiage or restrictive language. When writing surveys, the language needs to be appropriate and relevant for the audience, the survey itself and the particular user mindset.

As an example, I would like to cite the survey that one of our clients, a dieting website, created. In it they used industry jargon through the inclusion of terms such as VLCD and Ketosis. Not being dieting experts, we were unaware of the meaning of such terminology. When we reviewed the language used within the survey with the targeted respondents, we found that 20% did not know what these terms meant. This resulted in an ambiguous situation – were the terms not relevant to the target audience or was is that these respondents were not relevant to the survey?

Indeed, My Market Research Methods stated in an article from 2011 “when constructing your survey language, use common, simple words that have little room for interpretation”. Words such as “often”, “sometimes” and “recently” are all open to interpretation and mean different things to different people. For example, if you asked “did you recently buy car insurance” as opposed to “did you recently go food shopping”, the mindset of the audience is different and relates to the product in question. The term “recently” in car insurance could mean ‘months’ whereas the same term used in a context of food shopping could mean ‘days’; but even that in itself is subjective.

4. Audience

Very much related to the language of a user survey, is the audience for whom it is targeted towards. The language of a survey question or questions can heavily bias a user’s response (we all know the power of copywriting, right?). In simpler words, who you are asking is just as important as how you are asking.

For example, at my workplace, we always survey both prospective customers and actual customers as they are two totally different user personas who have different, albeit arguably similar, voices (known as voice of the customer – VOC). Our segmentation can be much more advanced than this. Users who purchased 6 months ago in contrast to those who have just purchased, will most likely have varying responses. In this regard, the design of the survey should be more targeted towards eliciting the best and most useful information out of each segment.

Take for example, Monthly1k.com by Noah Kagan (great post by the way!), who in a bid to get a better understanding of their users, Kagan stated “it was WHO I surveyed that proved to be the most helpful.” He surveyed those who opened the email, clicked on it, but did not buy – asking them only 4 questions.

5. Survey Length

All of the above mistakes actually culminate in making a survey too long. If you know how to write a survey correctly, you can be much more efficient with your questions and therefore elicit the right answers, quicker.

The effect of a long survey? – a low conversion rate and what Dr Rob Balon refers to as “the error of central tendency”. In short, this error occurs when mental fatigue sits in. In fact, the term “central tendency” relates to the point when, in a scale of 1 to 5, users pick 3 the most often (admit it, we have all been there).

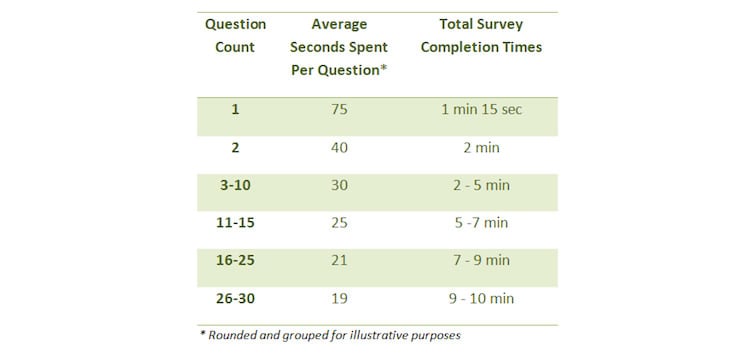

Survey Monkey found back in 2011 that “the relationship between the number of questions in a survey and the time spent answering each question is not linear”. The more questions you ask, the the less time your respondents spend answering them. So what is the appropriate length of a survey? Well from our experience, the answer is – it is context dependent. Therefore, the question should not be “what is the right number of questions to ask in a survey?” but “how should I calculate the number of questions to ask in my survey?”.

Conclusion

These are just 5 common mistakes we often see – through doing online surveys ourselves, seeing what others are doing or simply through researching. “Mistakes” as a term suggests what is wrong or what can be done right. However, in survey design, we are asking about perception and attitude of a user. Because of this level of subjectivity, is anything wrong or right? Indeed, these are guidelines we recommend you follow and there are some great blog posts on such a highly contentious subject.

Ultimately, ‘good’ user survey design (a highly subjective term in itself) comes down to understanding your business goals and how the survey itself can facilitate you accomplishing them.

Want to learn more?

If you’d like to improve your skills in User Research, then consider to take the online course User Research – Methods and Best Practices. Alternatively, there is an entire course on Usability Testing which includes templates you can use in your own projects. Lastly, if you want to brush up on the basics of UX and Usability, you might take the online course on User Experience. Good luck on your learning journey!

(Lead image: Depositphotos)