The Agile methodology has taken the software development world by storm over the last two decades, and with good reason. The focus on iterative and incremental development, cross-functional teams, and working software over laborious documentation fits well with our need to respond rapidly to an ever-changing technological landscape. However, the move to Agile has left many product owners, development teams, and user experience (UX) professionals scratching their heads over the best way to incorporate user-centered design into the process while balancing the demands of an aggressive development schedule.

At first, this might seem like an impossible task – how do you fit a usability study, which could take months to prepare, conduct, and report on, into a development cycle where the product is different after each sprint? Believe it or not, building a customer feedback loop into the Agile process is not only possible, but is a natural extension of the Agile philosophies of incremental changes and iterative development. However, building this feedback loop in takes some thoughtful changes to your team composition, work processes, and deliverables.

Because each Agile team works a little (or a lot!) differently, finding the right process for your team may take some experimentation. In the past decade, many organizations have begun reporting on their successes and challenges integrating UX work into their Agile process – see, for example, some of the seminal case studies by Desirée Sy and Lynn Miller, as well as Aviva Rosenstein’s more recent Boxes and Arrows article and Janet Six’s UXmatters article, both of which are based on interviews with UX experts working in Agile environments. Out of these case studies and interviews, some interesting trends and best practices have started to emerge.

If you are part of an Agile team seeking to add UX work into your current process, or if you are a UX professional working with a Waterfall development team that would like to convert to Agile, here are some practical tips and resources that can help you incorporate user-centered design into an Agile development process. These tips are based on trends I’ve seen reported in the UX literature (see references below for additional reading), which also resonate with my own experiences working with an Agile team.

1. Build a team of collaborative, cross-functional people

Work with your organization to build a team of people who are naturally curious about other disciplines, work well with others, and are flexible. The team should include everyone needed to get the project done – product owner, developers, analysts, quality assurance, UX specialists, designers, etc.

Agile is by nature a highly collaborative approach to project execution, and therefore requires team members who enjoy offering up their specialized insight into all aspects of the project work. Cross-functional teams provide multidisciplinary perspectives on all project ideas, which lead to better design solutions. If possible, co-locate team members to encourage interaction. However, when co-location is not possible or economical, having good remote meeting solutions works well too.

2. Bring UX researchers and designers onto the team from the very beginning of the project

Be sure to bring UX specialists and designers onto your team from the very beginning so they can help establish and test the big picture vision for the product, and help keep the team’s eye on this vision as the project unfolds. Bringing UX specialists onto your team early helps the team work together in setting up work processes that maximize collaboration and efficiency between the testers, designers, and developers. In addition, it gives the UX team members time to establish their own testing/design protocols and develop study participant lists, which is difficult to do in the thick of sprinting. (In the Agile world, a “sprint” is a set period of time during which specific work must be completed and made ready for review, usually a matter of a few weeks.)

3. Take a collaborative, not a siloed approach to doing the work

While team member specialists are still responsible for delivering their pieces of the work, the difference comes in how Agile teams approach the work. Teams that successfully integrate UX into their process do so by involving all team members in the usability studies and design work, and by iterating the design based on solutions agreed on by the team. UX specialists and designers, in turn, work hand in hand with analysts and developers as they build the design into a working product.

This type of close collaboration helps foster a shared vision for the product, build trust, and increase team efficiency. In addition, it helps ensure that the design is constantly accounting for the realities of development, while development is always informed by the user needs. Aviva Rosenstein’s Boxes and Arrows article cited above, The UX Professionals’ Guide to Working with Agile Scrum Teams, provides some recommendations for developing strong team relationships based on understanding of and respect for one another’s strengths.

4. Encourage experimentation

As Jeff Gothelf in his book Lean UX points out, “Permission to fail breeds a culture of experimentation. Experimentation breeds creativity. Creativity, in turn, yields innovative solutions.” Because there is no one-size-fits-all Agile methodology, it’s important to make sure the team has the freedom to experiment with their processes, deliverables, and sprint rhythm. Establish a culture where taking risks and progressive elaboration of team processes and deliverables is encouraged – after all, you’re unlikely to get it right the first time, but if you experiment, eventually you will.

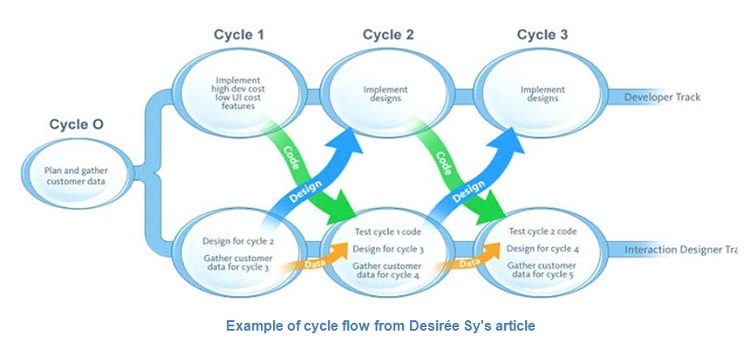

For example, some Agile UX practitioners advocate a staggered sprints approach to integrating UX and design activities with development activities, where design activities take place one or two sprints ahead of development work (as noted in both Lynn Miller’s and Desirée Sy’s articles). But Jeff Gothelf in Lean UX talks about the disadvantages his team encountered with this approach, and describes the experimentation they engaged in to find a sprinting process that allowed everyone to focus on the same problems at the same time. Your team can, and probably should, start with someone else’s model for incorporating UX work into the sprint cycle – but, like Jeff’s team, don’t be afraid to evolve your process to suit the needs of your team and your project.

5. Find the optimal sprint rhythm for your team

Establishing a sprint rhythm that allows the team to make adequate progress while maintaining a sustainable pace is critical. This is especially important when introducing UX activities into the sprinting process. Finding the right rhythm requires choosing the appropriate scope for each sprint, picking the right UX activities, figuring out how best to “chunk” the design work (Desirée Sy’s article has helpful advice on this), finding the right level of documentation, and playing with sprint duration.

Ultimately, the sprint rhythm will depend on the team and the project. For example, some teams might find that a two-week sprint cycle with UX testing every other sprint works well for them; others may prefer a three- or four-week sprint cycle with testing during every sprint. As mentioned above, some teams might prefer to use a staggered sprint approach to incorporating UX activities into the sprint rhythm; others may prefer a model more like the one Jeff Gothelf describes.

6. Make sure user experience activities are focused and actionable

Working on Agile time scales necessitates modifying the timing and granularity of UX activities that are performed. For example, your team may need to:

- Streamline study planning processes.

- Develop smaller-scale studies that focus on a few key design elements.

- Test on low-fidelity mock-ups instead of polished prototypes (see Garett Dworman’s UsabilityGeek blog post for more on the advantages of using low-fidelity mock-ups to iterate design solutions).

- Use methodologies such as the Rapid Iterative Testing and Evaluation (RITE) method to test and iterate designs more quickly.

- Supplement formal usability testing with quick-turnaround online tests using products like User Testing, or through informal tests using in-house participants (especially when testing early designs).

- Think about faster ways to recruit members of your target audience to participate in more formal studies (for example, creating a bank of participants available for studies).

To be sure the UX activities meet your team’s informational needs, all team members must be involved in articulating the study questions for each round of UX testing. Once the results are in, the whole team should go through the findings and come up with realistic, actionable solutions to the issues identified.

7. Experiment with appropriate quality for user experience study materials and deliverables

While long and detailed documentation has its place, Agile values “working software over comprehensive documentation” (see the Manifesto for Agile Software Development). Values like this plus short release cycles means there is rarely time to write a tome – by the time you finish writing, your report will be moot. So instead, UX practitioners working on Agile teams need to think creatively about how they can produce lighter-weight study materials and deliverables that give the team only what they need in order to move forward. For example, in her article, Desirée Sy talks about using verbal stories and demonstrations of observed behavior, along with index cards documenting each issue, to communicate test results to her team.

Findings should be succinct and prioritized by the team so everyone buys into the findings and knows which problems to focus on first and which should go into the backlog. In Janet Six’s interview with Carol Barnum, Carol describes her team’s process of debriefing together at the end of each study day to “agree on the findings and prioritize the issues the development team needs to fix. The developers, when present, walk out with their list of issues to address in the next or a future sprint.” If done properly, light-weight reporting is by no means synonymous with lack of quality; it is simply a different, and often more effective, way to communicate your results.

References and Resources

If you and your team would like to learn more about this topic, take a look at the following references and resources:

- Agile Development and User Experience (class offered by the Nielsen Norman Group)

- Beck, K., Beedle, M., van Bennekum, A., Cockburn, A., Cunningham, W., Fowler, M., Grenning, J., Highsmith, J., Hunt, A., Jeffries, R., Kern, J., Marick, B., Martin, R.C., Mellor, S., Schwaber, K., Sutherland, J., Thomas, D. (2001), Manifesto for Agile Software Development.

- Dworman, G. (2014), When To Prototype, When To Wireframe – How Much Fidelity Can You Afford? UsabilityGeek.com.

- Gothelf, J. (2013), Lean UX: Applying Lean Principles to Improve User Experience. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media, Inc.

- Medlock, M.C., Wixon, D., Terrano, M., Romero, R., and Fulton, B. (2002), Using the RITE method to improve products: A definition and a case study. Presented at the Usability Professionals Association 2002 Conference, Orlando, FL.

- Miller, L. (2005), Case Study of Customer Input for a Successful Product. Proceedings of Agile 2005. Denver: Agile Alliance.

- Rosenstein, A. (2013), The UX Professionals’ Guide to Working with Agile Scrum Teams. Boxesandarrows.com.

- Six, J.M. (2011), Integrating UX into Agile Development. UXmatters.com.

- Sy, D. (2007), Adapting Usability Investigations for Agile User-centered Design. Journal of Usability Studies, Vol. 2(3), pp. 112-132.

Want to learn more?

If you’d like to improve your skills in User

Research, then consider taking the online course User

Research – Methods and Best Practices. The course certificate is recognized

by industry and it will help you advance your career. Alternatively, there is

an entire

course on Usability Testing which includes templates you can use in your

own projects. Lastly, if you want to brush up on the basics of UX and

Usability, you might take the online

course on User Experience. Good luck on your learning journey!